Tibetan Buddhism

Tibetan Buddhism is the body of Buddhist religious doctrine and institutions characteristic of Tibet, Mongolia, Tuva, Bhutan, Kalmykia and certain regions of the Himalayas, including northern Nepal, and India (particularly in Arunachal Pradesh, Ladakh, Lahaul and Spiti in Himachal Pradesh, and Sikkim). It is the state religion of Bhutan. It is also practiced in Mongolia and parts of Russia (Kalmykia, Buryatia, and Tuva) and Northeast China. Texts recognized as scripture and commentary are contained in the Tibetan Buddhist canon, such that Tibetan is a spiritual language of these areas. A Tibetan diaspora has spread Tibetan Buddhism to many Western countries, where the tradition has gained popularity. The number of its adherents is estimated to be between ten and twenty million.

Buddhahood

Tibetan Buddhism comprises the teachings of the three vehicles of Buddhism: the Foundational Vehicle, Mahāyāna, and Vajrayāna. The Mahāyāna goal of spiritual development is to achieve the enlightenment of Buddhahood in order to most efficiently help all other sentient beings attain this state. The motivation is the bodhicitta mind of enlightenment — an altruistic intention to become enlightened for the sake of all sentient beings. Bodhisattvas are revered beings who have conceived the will and vow to dedicate their lives with bodhicitta for the sake of all beings. Tibetan Buddhism teaches methods for achieving Buddhahood more quickly by including the Vajrayāna and Mahāyāna paths. Buddhahood is defined as a state of mind free from obstructions to liberation and omniscience. When Buddhahood is reached, one is freed from all mental obscurations and is said to attain a state of continuous bliss, mixed with a simultaneous cognition of emptiness; which is the true nature of reality. In this state, all limitations on one's ability to help other living beings are removed. It is said that there are countless beings who have attained Buddhahood. Buddha's spontaneously, naturally and continuously perform activities to benefit all sentient beings. However it is believed that one's karma could limit the ability of the Buddha to help them. Thus, although Buddhas possess no limitation on their ability to help others, sentient beings continue to experience suffering as a result of the limitations from their own former negative actions.

General methods of practice

Transmission and realization

There is a long history of oral transmission in the teachings of Tibetan Buddhism. Oral transmissions by lineage holders traditionally can take place in small groups or mass gatherings of listeners and may last for seconds (in the case of a mantra, for example) or months (as in the case of a section of the canon). A transmission can even occur without actually hearing, as in Asaṅga's visions of Maitreya. An emphasis on oral transmission as more important than the printed word, derives from the earliest period of Indian Buddhism, when it allowed teachings to be kept from those who should not hear them. Hearing a teaching (transmission) readies the hearer for realization. The person from whom one hears the teaching should have heard it as one link in a succession of listeners going back to the original speaker: the Buddha in the case of a sutra or the author in the case of a book. Then the hearing constitutes an authentic lineage of transmission. Authenticity of the oral lineage is a prerequisite for realization, hence the importance of lineages.

The teaching of Buddha

Analytic meditation and fixation meditation

Spontaneous realization on the basis of transmission is possible but rare. Normally an intermediate step is needed in the form of analytic meditation, i.e., thinking about what one has heard. As part of this process, entertaining doubts and engaging in internal debate is encouraged in some traditions. Analytic meditation is just one of two general methods of meditation. When it achieves the quality of realization, one is encouraged to switch to "focused" or "fixation" meditation. In this, the mind is stabilized on that realization for periods long enough to gradually habituate it to it. A person's capacity for analytic meditation can be trained with logic. The capacity for successful focused meditation can be trained through calm abiding. A meditation routine may involve analytic meditation to achieve deeper levels of realization, with alternating sessions of focused meditation to consolidate them. The deepest level of realization is Buddhahood itself.

Devotion to a Guru

As in other Buddhist traditions, an attitude of reverence for the teacher, or guru, is also highly prized. At the beginning of a public teaching, a lama will do prostrations to the throne on which he will teach due to its symbolism, or to an image of the Buddha behind that throne. The students will do prostrations to the lama after he is seated. Merit accrues when one's interactions with the teacher are imbued with such reverence in the form of guru devotion, a code of practices governing them that derives from Indian sources. By such things as avoiding disturbance to the peace of mind of one's teacher, and wholeheartedly following his prescriptions, accrues much merit and can significantly help improve one's practice.

There is a general sense in which any Tibetan Buddhist teacher is called a lama. A student may have taken teachings from many authorities and revere them all as lamas in this general sense. However, he will typically have one held in special esteem as his own root guru and is encouraged to view the other teachers who are less dear to him, however more exalted their status, as embodied in and subsumed by the root guru. Often the teacher the student sees as root guru is simply the one who first introduced him to Buddhism, but a student may also change his personal view of which particular teacher is his root guru any number of times.

Skepticism

Skepticism is an important aspect of Tibetan Buddhism, an attitude of critical skepticism is encouraged to promote abilities in analytic meditation. In favour of skepticism towards Buddhist doctrines in general, Tibetans are fond of quoting sutra to the effect that one should test the Buddha's words as one would the quality of gold.

The opposing principles of skepticism and guru devotion are reconciled with the Tibetan injunction to scrutinise a prospective guru thoroughly before finally adopting him as such without reservation. A Buddhist may study with a lama for decades before finally accepting him as his own guru.

Preliminary practices and approach to Vajrayāna

The Vajrayāna deity, Vajrasattva

Vajrayāna is acknowledged to be the fastest method for attaining Buddhahood, but for unqualified practitioners it can be dangerous. To engage in it, one must receive an appropriate initiation (also known as an "empowerment") from a lama who is fully qualified to give it. From the time one has resolved to accept such an initiation, the utmost sustained effort in guru devotion is essential. The aim of preliminary practices (ngöndro) is to start the student on the correct path for such higher teachings. Just as Sutrayāna preceded Vajrayāna historically in India, so sutra practices constitute those that are preliminary to tantric ones. Preliminary practices include all Sutrayāna activities that yield merit like hearing teachings, prostrations, offerings, prayers and acts of kindness and compassion, but chief among the preliminary practices are realizations through meditation on the three principle stages of the path: renunciation, the altruistic bodhicitta wish to attain enlightenment and the wisdom realizing emptiness. Without the foundation of these three stages, attempting the practice of Vajrayāna would be like a small child trying to ride a wild horse. While the practices of Vajrayāna are not known in Sutrayāna, all Sutrayāna practices are common to Vajrayāna. Without training in the preliminary practices, the ubiquity of allusions to them in Vajrayāna is meaningless and even successful Vajrayāna initiation becomes impossible. The merit acquired in the preliminary practices facilitates progress in Vajrayāna. While many Buddhists may spend a lifetime exclusively on sutra practices, an amalgam of the two is common, to a degree. For example, in order to train in calm abiding, one might use a tantric visualisation as the meditation object.

Tibetan Tantrism is a form of practical Buddhism abounding in methods and techniques for carrying out the practice of all Mahayana teachings. In contrast to the “theoretical” forms of Buddhism such as Sautrantika, Vaibhasika, Madhyamika, Yogacara, Hua Yen, Tien Tai, etc., Tibetan Tantrism lays most of its stress on Practice and Realization, rather than on philosophical speculations. Its central principles and practices may be summarized as follows:

1. That all existence and manifestation can be found in one’s experience, that that experience is with one’s own mind, and that Mind is the source and the creator of all things. 2. That Mind is an infinitely vast, unfathomably deep complex of marvels, its immensity and depth being inaccessible to the uninitiated. 3. That he who has come a thorough realization and perfect mastership of his own mind is Buddha, and that those who have not done so are unenlightened sentient beings. 4. That sentient beings and Buddhists are, in essence, identical. Buddhas are enlightened sentient beings, and sentient beings are unenlightened Buddhas. 5. That this infinite, all-embracing Buddha-Mind is beyond comprehension and attributes. The best and the closest definition may be: “Buddha-Mind is a GREAT ILLUMINATING-VOID AWARENESS” 6. That the consciousness of sentient beings is of limited awareness; the conscious of an advanced yogi, of illuminating awareness; the consciousness of an enlightened Bodhisattva, of illuminating-void awareness; and the “consciousness” of Buddha, the GREAT ILLUMINATING-VOID AWARENESS. 7. That all Buddhist teachings are merely “exaltations” preparations, and directions leading one toward the unfoldment of this GREAT ILLUMINATING-VOID AWARENESS. 8. That the infinite compassion, merit, and marvels will spontaneously come forth when this Buddha-Mind is fully unfolded. 9. That to unfold this Buddha-Mind, two major approaches or Paths are provided for differently disposed individuals: the Path of Means, and the Path of Liberation. The former stresses an approach to the Buddhahood through the practice of taming the Prana, and the latter an approach through the practice of taming the mind. Both approaches, however, are based on the truism of the IDENTICALITY OF MIND AND PRANA. (T.T.: Rlun.Sems.dWyer.Med.), which is the fundamental theorem of Tantrism.

The principle of the Identically of the Mind and Prana may be briefly stated thus: The world encompasses and is made up of various contrasting forces in an “anthentical” form of relationship – positive and negative, noumenon and nonfenomenon, potentiality and manifestation, vitality and voidness, Mind and Prana, and the like. Each of these dualities, though apparently antithentical, is an inseparable unity. The dual forces that we see about us are, are, in fact, one “entity” manifesting into two different forms of stages. Hence, if ones consciousness or mind is disciplined, tamed, transformed, extended, sharpened, illuminated, and sublimated, so will be his Pranas, and vice versa. The practice that stresses taming the Prana is so called the “Yoga of Form”, or the “Path of Means. The practice that stresses taming the mind is called the “Yoga without form”, or the “Path of Liberation”. The former is an exertive type of Yoga practice, and the latter a natural and effortless one, know as Mahamudra.

(1)The Path of Means: The main practices of the Path of Means containing the following eight steps: (A) The cultivation of altruistic thoughts, and the basic training in the discipline of the Bodhisattva. (B) The four fundamental preparatory practices, which contain: (a) One hundred thousand obeisances to the Buddhas. This practice is for the purpose of cleansing all bodily sins and hindrances, thus enabling to meditate without being handicapped by physical impediments. (b) One hundred thousand recitations of repentance prayers. When properly performed, this cleanses mental obstructions and sins, clearing out all mental hindrances that may block spiritual growth. (c) One hundred thousand repetitions of the prayer to one’s Guru of the Guru Yoga Practice. This brings protection and blessings from one’s Guru. (C) The patron Buddha Yoga, a training for identifying and unifying oneself with a divine Buddha as assigned to one by his Guru. This Yoga consists of mantra recitations, visualization, concentration, and breathing exercises. (D) The advanced form of breathing exercises and their conmitant and subsidiary practices, including the Yogas of dream, of transformation, of Union, and of Light – generally known as the Perfecting Yogas. (E) Guiding the subtle Prana-Mind (T.T.:Rlun.Sems.) into the Central Channel, thus successively opening the four main Cakras (“psychic” centers) and transforming the mundane consciousness into transcendal Wisdom. (F) Applying the power of Prana-Mind to bring about or to vanquish at will, one`s death, Bardo, and reborn state, thus achieving emancipation from Samsara. (G) Applying the power to Prana-Mind to master the mind-projection performances. (H) Subliming and perfecting the Prana-Mind into the Three Bodies of Buddhahood. (2) The path of Liberation, or the Yoga without form, is the simplest and the most direct approach toward the Buddha-Mind. It is a natural and spontaneous practice, by passing many preparations, strenuous exercises, and even successive stages as laid down in other types of Yoga. Its essence consists in the Guru’s capability of bringing to his disciple a glimpse of the Innate Buddha-Mind in its primordial and natural state. With this initial and direct “glimpsing experience”, the disciple gradually learns to sustain, expand, and deepen his realization of this Innate Mind. Eventually he will consummate this realization to its full blossoming in Perfect Enlightenment. This practice is called Mahamudra. (A) The first glimps of the Innate Mind can be acquired either through practicing Mahamudra Yoga by oneself, or through receiving a “Pointing-out” demonstration from one`s Guru. The former way is to follow the Guru’s instructions and meditate alone; the latter consists of an effort by the Guru to open the disciple mind instantaneously Both approaches, however, require the continuous practice of Mahamudra Yoga to deepen and perfect one`s experience. (B) The central teaching of Mahamudra consists two major points: relaxation, and effortlessness. All pains and desires are of a tense nature. But Liberation, in contrast, is another name for “perfect relaxation”. Dominated by long-established habits, average people find it most difficult, if not entirely impossible, to reach a state of deep relaxation; so instructions and practices are needed to enable them to attain such a state. The primary concern of Mahamudra, therefore, is to instruct the yogi on how to relax the mind and thus induce the unfolding of his Primordial Mind. Paradoxically, effortlessness is even more difficult to achieve that relaxation. It requires long practice to become “effortless” at all times and under circumstances. If one can keep his mind always relaxed, spontaneous, and free from clinging, the Innate Buddha-Mind will soon down upon him. (3) The path of Means and The path of Liberation, exist only in the beginning stages. In the advanced stages these two Paths converge and become one. It is to the advantage of a yogi, in order to hasten his spiritual progress, if he can either practice both teachings at the same time or use one to supplement the other. Most of the great yogis of Tibet practiced both Paths, as did Milarepa.”

Esotericism

A sand mandala

In Vajrayāna particularly, Tibetan Buddhists subscribe to a voluntary code of self-censorship, whereby the uninitiated do not seek and are not provided with information about it. This self-censorship may be applied more or less strictly depending on circumstances such as the material involved. A depiction of a mandala may be less public than that of a deity. That of a higher tantric deity may be less public than that of a lower. The degree to which information on Vajrayāna is now public in western languages is controversial among Tibetan Buddhists.

Wrathful bodhisattvas

The most distinctive point in Tibetan Buddhism is the concept of the Wrathful (or Terrifying) bodhisattvas. Coming from the concept of Vajyarana that "Everything" is Voidness, and thus in Vajrayana monks not only work with concepts of "Good"; but they also work with concepts of "Evil". In Vajrayana Buddhism both "good" and "evil" aspects are mixed together, and people and lamas work and study with all of them. The most important consequence from this is that occasionally lamas are involved in scandals, corruption or crimes, because they act as Wrathful bodhisattvas like Mahakala, Yamantaka, Dorje Phagmo, Vajrapani and others. Wrathful in Tibetan is said Dragpo or Drakpo. The symbol of these Terrifying boddhisattvas is the kapala: a half skull filled with blood.

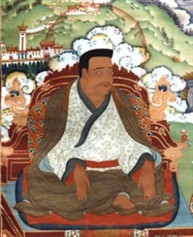

Reincarnating lamas: the Tulkus

![In Tibetan Buddhism, a tulku (Tibetan: སྤྲུལ་སྐུ, Wylie: sprul sku, ZYPY: Zhügu, also tülku, trulku) is an honorary title given to a recognised reincarnate Lama either on the grounds of his (her) resembling an enlightened being or through his (her) connection to certain qualities of an enlightened being. Amongst the Tulkus of Tibet are those who are reincarnations of superior Bodhisattvas, who are able to choose their place and time of birth as well as their future parents.[1] High-profile examples of tulkus include the Dalai Lama, the Panchen Lama and the Karmapa.](images/karmapa16.jpg)

Another important point in Tibetan Buddhism is the famous concept of the Tulku or Trulku, which means that lamas make a "reincarnation", and the disciples look for the child as the new "body" of their old master. The word "tulku" literally means Body of Emanation; in Sanskrit is Nirmanakaya.

Native Tibetan developments

Some commentators have emphasised Tibetan innovations such as the system of incarnate lamas. True to its roots in the Pāla system of North India, Tibetan Buddhism carried on a tradition of eclectic accumulation and systematisation of diverse Buddhist elements, and pursued their synthesis. Prominent among these achievements are the Stages of the Path and motivational training.

Study of tenet systems

Monks debating

Tibetan Buddhists practice one or more understandings of the true nature of reality, the emptiness of inherent existence of all things. Emptiness is propounded according to four classical Indian schools of philosophical tenets.

Two belong to the older path of the Foundation Vehicle: Vaibhaṣika (Tib. bye-brag smra-ba) Sautrāntika (Tib. mdo-sde-pa)

The primary source for the former is the Abhidharma-kośa by Vasubandhu and its commentaries. The Abhidharmakośa is also an important source for the Sautrāntikas. Dignāga and Dharmakīrti are the most prominent exponents.

The other two are Mahayana (Skt. Greater Vehicle) (Tib. theg-chen): Yogācāra, also called Cittamātra (Tib. sems-tsam-pa), Mind-Only Madhyamaka (Tib. dbu-ma-pa)

Yogacārins base their views on texts from Maitreya, Asaṅga and Vasubandhu, Madhyamakas on Nāgārjuna and Āryadeva. There is a further classification of Madhyamaka into Svatantrika-Madhyamaka and Prasaṅgika-Madhyamaka. The former stems from Bhavaviveka, Śāntarakṣita and Kamalaśīla, and the latter from Buddhapālita and Candrakīrti.

The tenet system is used in the monasteries and colleges to teach Buddhist philosophy in a systematic and progressive fashion, each philosophical view being more subtle than its predecessor. Therefore the four schools can be seen as a gradual path from a simpler "realistic" philosophical point of view, to increasingly complex and subtle views on the ultimate nature of reality; that is on emptiness and dependent arising, culminating in the philosophy of the Mādhyamikas, which is widely believed to present the most sophisticated point of view.

The termas

A surprising development of the text study is the Terma texts. Termas (Treasury Texts) are texts composed by great Lamas; but which are hidden away and occulted to everybody, because it is not the time for the text to be revealed. When the appropriate time will come (often many years), the monks will discover the hidden text; when the world is ready for it.

History

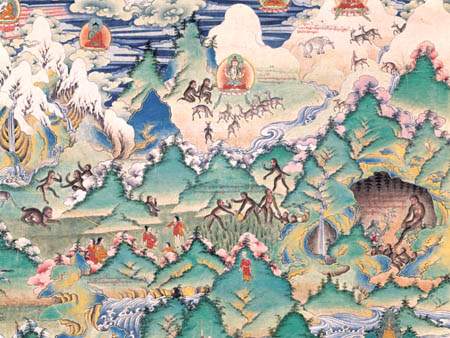

Early history

In the reign of King Thothori Nyantsen (5th century CE), a basket of Buddhist scriptures arrived in Tibet from India. Written in Sanskrit, they were not translated into Tibetan until the reign of king Songtsän Gampo (618-649). While there is doubt about the level of Songtsän Gampo's interest in Buddhism, it is known that he married a Nepalese Buddhist princess, Bhrikuti. Songtstan Gampo also married a Chinese Tang Dynasty Buddhist princess, Wencheng, who came to Tibet with a statue of Shakyamuni Buddha. It is clear from Tibetan sources that some of his successors became ardent Buddhists. By the second half of the 8th century he was already regarded as an embodiment of the BodhisattveAvalokitesvare.

The successors of Songtsän Gampo were less enthusiastic about the propagation of Buddhism but in the 8th century, King Trisong Detsen (755-797) established it as the official religion of the state. He invited Indian Buddhist scholars to his court. In his age, the famous tantric mystic Padmasambhāva arrived in Tibet. In addition to writing a number of important scriptures, some of which he hid for future tertons to find, Padmasambhāva, along with Śāntarakṣita, established the Nyingma school.

During this early time, the influence of scholars under the Pāla dynasty in the Indian state of Magadha, came from the south. They had achieved a blend of Mahāyāna and Vajrayāna that has come to characterize all forms of Tibetan Buddhism. Their teachings were in sutra centered on the Abhisamayālankāra, a 4th century Yogācārin text. However, the Mādhyamika scholars Śāntarakṣita and Kamalaśīla were also prominent among them. A third influence was that of the Sarvāstivādins from Kashmir in the south west and Khotan in the north west. Although they did not succeed in maintaining a presence in Tibet, their texts found their way into the Tibetan Buddhist canon, providing the Tibetans with almost all of their primary sources about the Foundation Vehicle. A subsect of this school, Mūlasarvāstivāda was the source of the Tibetan vinaya.

Padmasambhāva, founder of the Nyingmapa, the earliest school of Tibetan Buddhism; note the wide-open eyes, characteristic of a particular method of meditation.

Later history

![Lozang Gyatso, the Great Fifth Dalai Lama, started the construction of the Potala Palace in 1645[2] after one of his spiritual advisers, Konchog Chophel (died 1646), pointed out that the site was ideal as a seat of government, situated as it is between Drepung and Sera monasteries and the old city of Lhasa.[3] It may overlay the remains of an earlier fortress, called the White or Red Palace,[4] on the site built by Songtsen Gampo in 637.[5] Today, the Potala Palace is a museum.](images/Potala Palace02.jpg)

Atiśa From the outset, Buddhism was opposed by the native shamanistic Bön religion, which had the support of the aristocracy, but with royal patronage it thrived to a peak under King Rälpachän (817-836). Terminology in translation was standardised around 825, enabling a translation methodology that was highly literal. Despite a reversal in Buddhist influence which began under King Langdarma (836-842), the following centuries saw a colossal effort in collecting available Indian sources, many of which now exist only in Tibetan translation. Tibetan Buddhism exerted a strong influence from the 11th century AD among the peoples of Inner Asia, especially the Mongols. It was adopted as an official state religion by the Mongol Yuan dynasty and the Manchu Qing dynasty that ruled China. The Mongols may have been attracted to the Lamaist tradition and responded the way they did due to the Lamaist's superficial culture similarities with the Mongol's shamanist culture. Even with this attraction, however, the Mongols "paid little attention to the fine points of Buddhist doctrine." Coinciding with the early discoveries of "hidden treasures" (terma), the 11th century saw a revival of Buddhist influence originating in the far east and far west of Tibet. In the west, Rinchen Zangpo (958-1055) was active as a translator and founded temples and monasteries. Prominent scholars and teachers were again invited from India. In 1042 Atiśa arrived in Tibet at the invitation of a west Tibetan king. This renowned exponent of the Pāla form of Buddhism from the Indian university of Vikramaśīla later moved to central Tibet. There his chief disciple, Dromtonpa founded the Kadampa school of Tibetan Buddhism, under whose influence the New Translation schools of today evolved.

Tibetan Buddhism has four main traditions:

Nyingma(pa), “the Ancient Ones”. This is the oldest, the original order founded by Padmasambhāva and Śāntarakṣita. Whereas other schools categorize their teachings into the three vehicles: The Foundation Vehicle, Mahāyāna and Vajrayāna, the Nyingma tradition classifies its into nine vehicles, among the highest of which is that known as Atiyoga or Dzogchen (“Great Perfection”). Hidden treasures (terma) are of particular significance to this tradition.

Kagyu(pa), “Lineage of the (Buddha's) Word”. This is an oral tradition which is very much concerned with the experiential dimension of meditation. Its most famous exponent was Milarepa, an 11th century mystic. It contains one major and one minor subsect. The first, the Dagpo Kagyu, encompasses those Kagyu schools that trace back to the Indian master Naropa via Marpa, Milarepa and Gampopa and consists of four major sub-sects: the Karma Kagyu, headed by a Karmapa, the Tsalpa Kagyu, the Barom Kagyu, and Pagtru Kagyu. There are a further eight minor sub-sects, all of which trace their root to Pagtru Kagyu and the most notable of which are the Drikung Kagyu and the Drukpa Kagyu. The once-obscure Shangpa Kagyu, which was famously represented by the 20th century teacher Kalu Rinpoche, traces its history back to the Indian master Naropa via Niguma, Sukhasiddhi and Kyungpo Neljor.

Sakya(pa), “Grey Earth”. This school very much represents the scholarly tradition. Headed by the Sakya Trizin, this tradition was founded by Khon Konchog Gyalpo, a disciple of the great translator Drokmi Lotsawa and traces its lineage to the Indian master Virupa. A renowned exponent, Sakya Pandita 1182–1251CE was the great grandson of Khon Konchog Gyalpo.The Three Sakya Schools: The main Sakya school to this day is under the leadership of the Khon clan. The head of Sakyapa is the "Sakya Trizin" ("the holder of the Sakya throne"). From the main Sakya school, two distinctive sub-schools emerged. Ngorpa. Founded by Ngorchen Kunga Zangpo (1382-1457), Ngorpa emphasizes monastic discipline. Tsarpa, Founded by Tsarchen Losal Gyatso (1502-56), known for teachings preserved in the Thirteen Golden Texts of Tsar. Sakya Today The present head of Sakyapa is His Holiness the Sakya Trizin, Ngakwang Kunga Thekchen Palbar Samphel Ganggi Gyalpo. His Holiness was born in 1945 in Tsedong, Tibet, and is the 41st throne holder. He lives in Raipur, India, with his wife Dakmo Tashi Lhakyi. They have two sons.

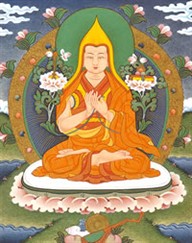

Gelug(pa), “Way of Virtue”. Originally a reformist movement, this tradition is particularly known for its emphasis on logic and debate. Its spiritual head is the Ganden Tripa and its temporal one the Dalai Lama. The Dalai Lama is regarded as the embodiment of the Bodhisattva of Compassion. Successive Dalai Lamas ruled Tibet from the mid-17th to mid-20th centuries. The order was founded in the 14th to 15th century by Je Tsongkhapa, renowned for both his scholasticism and his virtue.

These major schools are sometimes said to constitute the ”Old Translation” and ”New Translation” traditions, the latter following from the historical Kadampa lineage of translations and tantric lineages. Another common differentiation is into "Red Hat" and "Yellow Hat" schools. The correspondences are as follows: Nyingma, Kagyu, Sakya, and Gelug

| Old Translation | New Translation | New Translation | New Translation |

| Red Hat | Red Hat | Red Hat | Yellow Hat |

Besides these major schools, there is a minor one, the Jonang. The Jonangpa were suppressed by the rival Gelugpa in the 17th century and were once thought extinct, but are now known to survive in Eastern Tibet. It has been recognized by the Dalai Lama as fifth living Buddhist tradition of Tibet. Thuken Chökyi Nyima's Crystal Mirror of Philosophical Systems is a classic history of the different schools provides broad and useful historical information. The pre-Buddhist religion of Bön has also been recognized by Tenzin Gyatso, the fourteenth Dalai Lama, as a principal spiritual school of Tibet. There is also an ecumenical movement known as Rimé.

Monasticism

Lamayuru monastery Although there were many householder-yogis in Tibet, monasticism was the foundation of Buddhism in Tibet. There were over 6,000 monasteries in Tibet. Monasteries generally adhere to one particular school. Some of the major centers in each tradition are as follows:

Nyingma The Nyingma lineage is said to have "six mother monasteries," although the composition of the six has changed over time: Dorje Drak, Dzogchen Monastery, Katok Monastery, Mindrolling Monastery, Palyul, Shechen Monastery Also of note is Samye — the first monastery in Tibet, established by Padmasambhāva and Śāntarakṣita

Kagyu Tibetan Buddhist monks at Rumtek Monastery in Sikkim. Many Kagyu monasteries are in Kham, eastern Tibet. Tsurphu, one of the most important, is in central Tibet, as is Ralung and Drikung. Palpung Monastery — the seat of the Tai Situpa and Jamgon Kongtrul Ralung Monastery—the seat of the Gyalwang Drukpa Surmang Monastery — the seat of the Trungpa tülkus Tsurphu Monastery — the seat of H.H. the Gyalwa Karmapa

Sakya Sakya Monastery — the seat of H.H. the Sakya Trizin

Gelug The three most important centers of the Gelugpa lineage which are also called 'great three' Gelukpa university monasteries of Tibet, are Ganden, Sera and Drepung Monasteries, near Lhasa: Ganden Monastery — the seat of the Ganden Tripa. Drepung Monastery — the home monastery of the Dalai Lama Sera Monastery Three other monasteries have particularly important regional influence: Mahayana Monastery — the seat of the H.H Kadhampa Dharmaraja (The 25th Atisha Jiangqiu Tilei), Nepal Tashilhunpo Monastery in Shigatse — founded by the first Dalai Lama, this monastery is now the seat of the Panchen Lama Labrang Monastery in eastern Amdo Kumbum Jampaling in central Amdo Great spiritual and historical importance is also placed on: The Jokhang Temple in Lhasa — said to have been built by King Songtsen Gampo in 647 AD, a major pilgrimage site

Tibetan Buddhism in the contemporary world

Today, Tibetan Buddhism is adhered to widely in the Tibetan Plateau, Nepal, Bhutan, Mongolia, Kalmykia (on the north-west shore of the Caspian), Siberia and Russian Far East (Tuva and Buryatia). The Indian regions of Sikkim and Ladakh, both formerly independent kingdoms, are also home to significant Tibetan Buddhist populations. In the wake of the Tibetan diaspora, Tibetan Buddhism has gained adherents in the West and throughout the world.